BLOG | Listening to the Antarctic: What Krill Fishing Acoustics Reveal About Predators and Biodiversity

By Dominik Bahlburg (Alfred Wegener Institute), Sebastian Menze (Institute of Marine Research), in collaboration with Gustav Kågesten (HUB Ocean)

Listening to the Antarctic: What Krill Fishing Acoustics Reveal About Predators and Biodiversity

The Antarctic krill fishery sits at the centre of an intense public debate. Krill are a keystone species in the Southern Ocean, supporting penguins, seals, whales, and a uniquely productive ecosystem. At the same time, the 2025 fishing season saw record krill catches, increasing pressure on managers to ensure decisions are grounded in solid ecological evidence.

Everyone agrees on one thing, better data on how krill fisheries interact with the wider ecosystem would greatly improve science-based management. Yet collecting the necessary data is difficult given the remoteness of the Southern Ocean and the high costs of operations.

But what if some of this information already exists, hidden in plain sight?

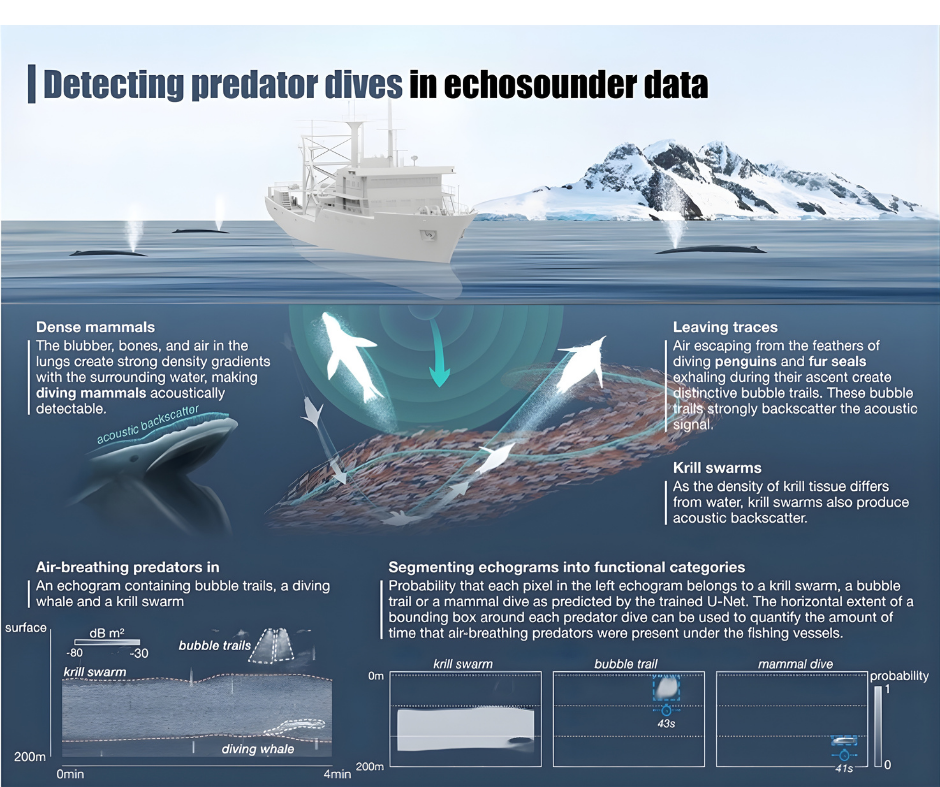

Krill fishing vessels rely on active acoustics to locate krill swarms. During normal fishing operations, vessels continuously transmit short sound pulses, or “pings,” into the water column and record the echoes that return when the sound encounters objects in the water, such as aggregations of krill. This process—similar to the echolocation used by bats or orcas to navigate and find prey—allows vessels to continuously scan the ecosystem beneath them.

The fisheries acoustics are typically treated as a by-product of fishing operations rather than a scientific resource. They often lack the standardized protocols of research-grade surveys, and as a result, their ecological potential has remained largely untapped. Yet these acoustic records provide something very valuable: a direct, high-resolution record of biological activity exactly where fishing is taking place.

Fig 1. Using fisheries acoustics to map encounter rates with krill-dependent predators.

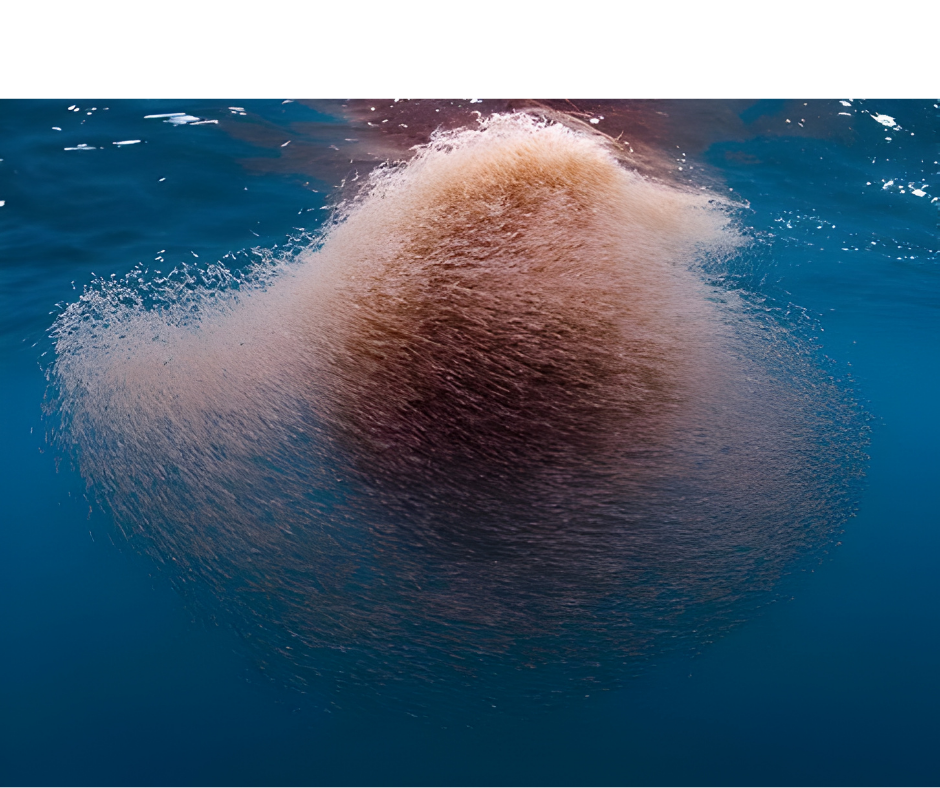

Crucially, the pings sent out by fishing vessels don’t just bounce off krill swarms. They can also bounce off penguins, fur seals, and whales that gather to feed on the same krill, adding to the echoes detected by the vessels. Because different organisms produce distinct echo shapes and intensities, these predator signals can be visually distinguished in echograms.

From massive amounts of raw acoustic fishery data to published scientific insights

Using raw acoustic fishery data shared by Aker QRILL Company, a recently published study (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2417203122) explored this idea by applying machine learning methods to krill fisheries acoustics data hosted by HUB Ocean and accessed through their Ocean Data Platform. The Ocean Data Platform enabled efficient access to large volumes of fisheries acoustics, making it possible to work with data at a scale that would otherwise be impractical. The following details the novel approach and important findings from the researchers themselves.

We trained a convolutional neural network for image analysis using more than 1,000 manually labelled echograms, each representing a standardized 10-minute snapshot of acoustic data and extending to 500 m depth. This segmentation model assigned a probability to each pixel of an echogram as belonging to krill swarms, penguins or seals, baleen whales, the seafloor, or background.

We then applied the trained model to more than 30,000 hours of fisheries acoustics available via the Ocean Data Platform, using optimized probability thresholds for the two predator classes, to identify acoustic signatures likely belonging to the predators.

Because this approach was still relatively experimental, model outputs were carefully cleaned to remove falsely identified predators. Control plots generated for every detected predator event proved essential during this validation step.

The result was a large and robust dataset of predator–vessel encounters, enabling us to identify areas and periods during which encounters with predators occurred most frequently. Each encounter marks an event of resource competition between the fishery and predators, and the frequency of encounters is potentially indicative of the intensity of this competition. This information would have been much more expensive to obtain through dedicated field campaigns.

A substantial part of the work took place before any ecological analysis could begin. Raw acoustic files from fishing vessels vary widely in format, resolution, and structure, often in manufacturer-specific and non-intuitive ways. Working within the Ocean Data Platform environment allowed us to standardize these datasets efficiently. We converted raw files to NetCDF format, transformed acoustic signals into standard backscatter units, resampled all data to a uniform time and depth resolution, and extracted vessel positions so each data point could be mapped geographically. This harmonization allowed us to use common Python tools such as Xarray and to scale the analysis efficiently using Dask.

To ensure we focused on periods of active fishing, we identified fishing activity using Global Fishing Watch. The neural network was applied to consecutive 10-minute acoustic snippets, producing prediction masks for every detected feature. When files were shorter or shallower than the standard window, missing data were padded with zeros to preserve the integrity of spatial patterns in the echograms.

So what did all this reveal?

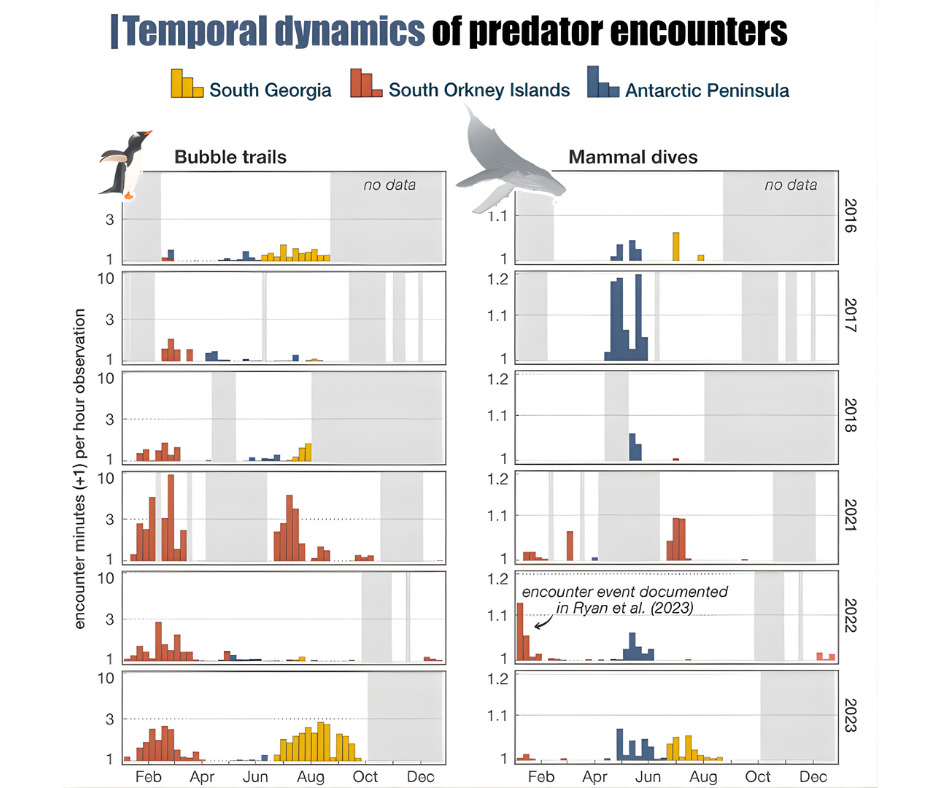

One of the most striking findings from our analysis was the clear predator-specific seasonality of encounter dynamics (Fig. 2). Encounters with penguins and seals occurred predominantly in summer and winter, while encounters with baleen whales peaked in autumn. Particularly surprising were the relatively high winter encounter rates for penguins and seals, as these species are often assumed to be widely dispersed during this period. Our spatial distribution patterns closely matched those derived from independent predator tracking studies, giving us confidence in the robustness of our approach. In addition, the analysis revealed previously unknown hotspots where predators and fishing vessels frequently overlap.

Fig. 2 Annual dynamics of fishing vessel-predator encounter rates.

Because krill fisheries acoustics are a cost-efficient by-product of routine operations, and because these data are now openly accessible through HUB Ocean and the Ocean Data Platform, this approach offers a powerful new way to assess predator–fishery interactions. Lightweight analyses could be completed within days or weeks after each fishing season, making it possible to rapidly detect trends, shifts, or emerging risks associated with changing fleet behaviour or environmental conditions.

More broadly, this work highlights the largely unexplored potential of fisheries acoustics as a tool for ecosystem monitoring. By re-purposing data that already exists and making them accessible through shared infrastructure such as the Ocean Data Platform, we can dramatically improve our understanding of how human activity intersects with biodiversity in one of the most remote regions on Earth, and take a meaningful step toward more transparent, adaptive, and ecosystem-based management of the Antarctic krill fishery.

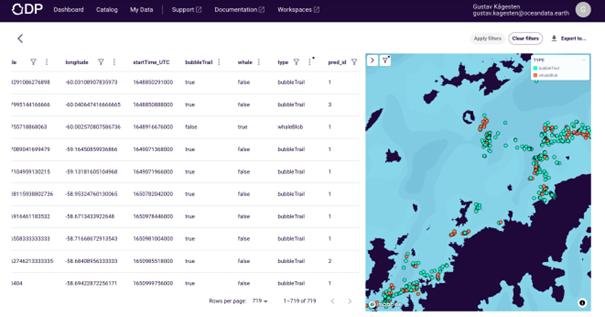

The published results are now also available through the Ocean Data Platform (ODP) where the detections of bubble trails from predators like penguins and fur seals and detection of whales can be explored and visualized on ODP Catalog, analyzed in ODP workspaces or downloaded. A sample notebook is provided to help you get started analyzing the acoustic data yourself directly in ODP workspaces or other data science environments.

Image 1. Tracklines of acoustic data collected during Aker QRILL company fishing operations

Image 2. Detections of predator e.g. bubble trails (pinguins, fur seals) and whales from data published by Dominik et al 2025, then ingested to the Ocean Data Platform.